Historically, the human form has

fascinated artists probably more than any other subject. Therefore it should

come as no surprise that the same fascination has extended to photography as

well.

While photography has generally been

accepted as a valid art form, photography of the nude to this day is struggling

with that recognition. In the view of

many, it is still looked upon as sleazy and objectionable, even harmful. No such objections exist when it comes to

paintings and sculptures. People

regularly visit art galleries. No

objections are generally voiced to see nude art there. Public spaces often display nude sculptures,

no objections there either. Yet nude

photographic art is still widely rejected.

Why?

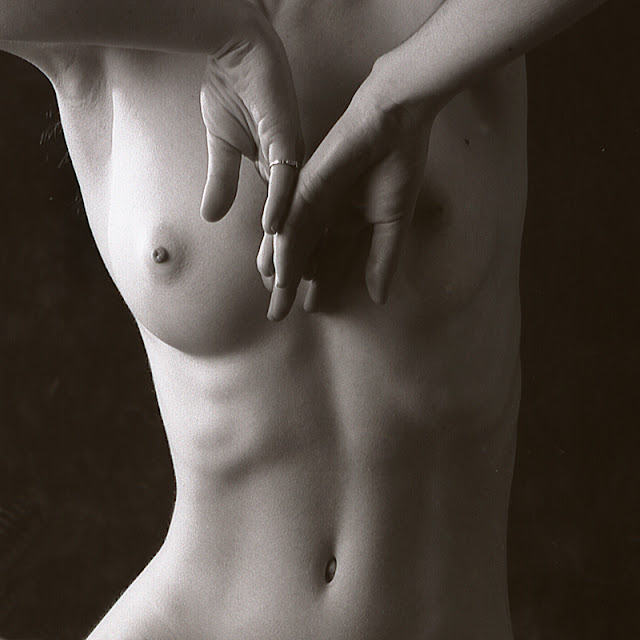

Heinz Richter

Marlies Amling

I must emphasize that the key word

here is art. Many of the great

photographers have produced fine art nudes like Alfred Stieglitz, Edward

Steichen, Edward Weston, Man Ray, Helmut Newton…, just to mention a few. Of course, just as with other art forms, some

like Robert Mapplethorpe or Jeff Koonz for instance have pushed the envelope by

producing images that are questionable to some, but such work should not be

generalized and held against other serious photographers.

I often discuss this with my sister

who is a successful professional photographer in Germany. She is often in disbelief how much more

restricted photography of this type is in the US. For instance, in her studio she has three

different display windows for her work, one of which is usually dedicated to

fine art nude photography. That is

simply unthinkable in the US.

Marlies Amling

That brings up the question of what

constitutes fine art nude photography.

During my 13 years of teaching photography that question regularly came

up during class discussions. Of course

the definition of art in general is in the eye of the beholder. There are no clear cut instructions to be

had.

Heinz Richter

Marlies Amling

Heinz Richter

When it comes to fine art nude

photography, it is quite easy to take a photograph of a person without any

clothes. That, however, is not art and

should not be attempted to be presented as such. Instead the emphasis should not be so much on

nudity but on shape, form, lighting, design and composition.

That adds a considerable amount of

difficulty which is further emphasized that in most cases, a similar approach

with similar results has been done before.

In an interview, Kim Weston, grandson

of Edward Weston, when asked about his photography in comparison to his

grandfather’s said that he generally does not think about him. He went on to say whatever kind of photograph

he might attempt, “Edward has done it.”

He said he cannot take a landscape without being told that Edward has done

it, he virtually cannot photograph anything without the constant reminder that

Edward has done it.

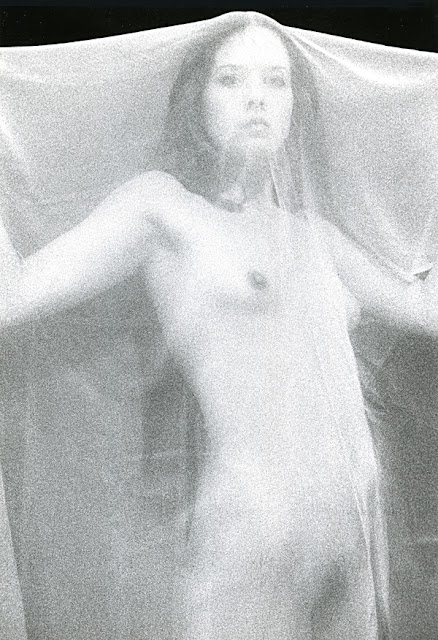

Marlies Amling

The same is the case with fine art

nude photography. Regardless of the

outcome, someone most likely has done it before and someone most likely will do

it again in the future.

The best approach in my opinion is to

carefully plan a fine art nude photography session and then proceed without too

much attention to the work of other photographers. Then careful selection of only the best

examples with a healthy dose of self-criticism should give the assurance that

the shoot was successful. And don’t

forget, the old adage the practice makes perfect still applies.

Heinz Richter

Heinz Richter

Heinz Richter

Heinz Richter

Blaine Schultz

As of late, Photoshop has opened

photographic possibilities that previously were impossible or at least very

difficult to achieve. But a lot of what

Photoshop has to offer, contrary to what many seem to assume, is not available

merely at the push of a button. Anyone

who has ever worked with Photoshop will agree that there is a considerable

learning curve; to master it certainly does not come overnight. However, one does not need to be afraid of

it. Photoshop definitely can be learned

to quite an extend simply by trial and error, although professional

instructions will definitely speed up the learning process.

Opinions about the system are

diverging to quite a degree. Some see it

as nothing more than a means to cover mistakes that occurred during

shooting. While many such mistakes can

definitely be corrected with Photoshop, it is not a panacea to everything that

might possibly go wrong. Just as in the

past, it is definitely advisable to strive to do everything correctly during a

shoot. That, of course, requires a

considerable base knowledge. As a matter

of fact, Photoshop should not al all be considered a means to become a good

photographer without knowing photography as such. Composition, posing, lighting, exposure

control, camera operation…., all are still as important today as they were in

the past and there is little that Photoshop can do to overcome those shortcomings.

Others criticize images modified with

the help of Photoshop as not original photography any longer. A colleague of mine recently claimed that

“real” photographs are only ones that are shown as they come out of the camera. I find that rather short sighted. Even in the past we used retouching and a

variety of darkroom trickery to alter the images as they came off the

negative. It was quite common to alter

the resulting photographs with changes in development, both film and paper. We used manipulative processes like

solarization, bas relief, posterization and a lot more to create images that

certainly differed substantially from what the lens put on film. Thus I find these criticisms quite out of

place.

The most important part of creating a

photographic image is the end result. How we arrive at that ultimately is

irrelevant.

Following are a number of images that

made extensive use of Photoshop, and while the results certainly required a lot

of work, it was ultimately a lot easier and less time consuming to create them

with the help of Photoshop than what would have been necessary to come up with

similar results during the “good old days.”

This Image is from an architectural photography assignment

Studio shoot of a model with very similar lighting

Combining the images rendered a great location shoot

The original image unfortunately is

lost. This image is the result of

modifying the original and making three identical copies, one of which was

right and left reversed and combining them in the manner shown

The three images above were combined to render this unusual result

The two base images were combined with considerable modification into this result

As I mentioned before, most topics of

photography are quite difficult to do if one tries to find a different

approach, something that has not been done by other photographers before. That is especially the case with fine art

nude photography. The nude has always

been a very popular theme of the arts, including photography. Regardless of how one approaches the subject,

it probably has been done in one form or another before.

I had been looking for such a

different approach for a long time, and finally decided to use Photoshop to

reach that goal. The result is

“Photosculptures,” where I use photographs of sculptures and combine them with

photographs I have taken of models.

That might not appear to be

particularly difficult. After all,

Photoshop is used to alter images in just about any imaginary way. However, Photosculptures require a lot more

than just replacing part of the sculpture with a photograph of a different

person. It is important that the pose of

the model and the lighting coincide with that of the sculpture, however, it is

not my intention to produce a perfect copy of the original. Then the two images have to be carefully

matched in size. Finally, the transferred

image has to be modified to match the color and texture of the sculpture. All of this is not an easy process, and it is

very time consuming. But the end results

can be quite rewarding.

This is the most difficult sculpture I modified, because it consists of three different individuals

The original, raw images of the three models, all taken with Leica equipment.

The original photograph of the three

models required considerable modifications.

All had to be right and left reversed.

Then all three had to be matched in size to the size of the sculpture. In addition, the posing angle of the models

was altered to match that of the sculpture. Then, after masking off the

background, the images of each model were transferred to the photograph of the

sculpture. Then each model was altered

to match the white marble of the sculpture.

That included lowering the contrast of the facial features and the hair

to again match the sculpture.

The finished Photosculpture

Original

Photosculpture

The original is a photograph of the

Rolls Royce hood ornament. Since the

pose of the model was not identical to that of the sculpture, it required

considerable modification of the hair flowing in the wind.

Original Photoscupture

This example required a considerable

amount of work. While the poses are

quite similar, the arms did not look right at all. It required to remove the hand on the arm of

the male which, in turn, required the arm of the male in the Photosculpture to

be lengthened. In addition, marble texture

and color was added to the Photosculpture.

Original Photosculpture

Even though the pose of the original

and the model are quite similar, this example required a considerable amount of

detail work. The upper arm of the model

had to be lengthened to match up with that of the original sculpture. The wing of the swan had to be lengthened a

lot to bridge the void that otherwise showed in front of the model’s face. In addition the head of the swan needed to be

moved further from the neck. Since the

position of the left arm of the sculpture and the model are quite different, a

fair amount of reconstructive work was necessary to cover the arm of the

original sculpture.

Original Photosculpture

This example was relatively easy to

convert. However, the strong lighting of

the original required close attention to the lighting of the model.

Accurate posing of the model

definitely makes this kind of work considerably easier. For that reason it is advisable to work with

experienced models that are able to strike a great variety of poses and do it

accurately once they see a sample of what pose is required. I have worked with most of the models shown

here on several occasions, with some of them even for several years. That has created a very good working

relationship which is also very helpful for this kind of work.

Regardless of what approach one

choses to take with these types of photography, none of it will come easy. Especially for a novice there is a lot to

learn and master. For that reason I want

to invite anyone interested to rely on my experience by asking questions,

whatever they might be. I’ll gladly help.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP

Photography

Click on ad to enlarge

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP

Photography

Click on ad to enlarge

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP

Photography

Photo: David Tenenbaum

Photo: David Tenenbaum