An interesting, but relatively unknown

fact is that NASA initially had chosen the Leica MDa as the camera to be used

on their lunar missions. The reason was

weight. Of all the systems for the

Apollo missions, one could never be tested because of the low gravity of the

moon. That was the take-off module. To gain as much of a weight advantage as

possible, NASA did everything they could to save weight. That included the camera equipment. The Leica MDa with 35mm f/1.4 Summilux was

definitely lighter than anything Hasselblad, their regular camera of choice,

had to offer. Leitz modified several

cameras and lenses to feature large levers to allow camera operation with the

bulky gloves of the space suits. The

astronauts chosen for the lunar missions all received extensive training in the

use of the camera.

NASA Leica MDa. Modifications appear to be a soft shutter

release, a larger shutter speed dial, an enlarged film wind lever a large rewind knob and an enlarged lever to open the camera. The top of the camera also has a beefed up plate with an accessory show attached. There is also an electronic connection of an unknown purpose in place of the PC connection.

Modifications of the lens are large levers

for the aperture and focus settings, all designed for easy operation with the gloves

of the space suits.

Yet, as is common knowledge, the Leica

never made it to the moon. The credit

goes to one engineer who figured out that the interchangeable film backs for

the Hasselblad were lighter than the Leica MDa with its Summilux lens. Subsequently NASA decided to use the Hasselblad

after all. The Saturn 5 rockets had no

problem delivering the payload to the moon.

For the return trip it was subsequently decided to remove the film backs

from the cameras and to leave the cameras and lenses on the moon where they

still reside today. A total of 12

Hasselblad cameras and lenses are sitting in the lunar dust, ready to be picked

up.

An intriguing question is if they might

be still able to operate properly after all these years in the extremely harsh

environment of the lunar surface.

Since then a few more details about the

NASA – Leica connection have emerged.

One virtually unknown fact is that NASA also used the Leicafelx SL. For what purpose is unknown at this point. I have also found that in 1966, NASA ordered

150 Leica cameras. Unfortunately it was

not stated which cameras they were.

The camera appears to be without visible

modifications other than the deeply knurled shutter speed dial to accommodate

the heavy gloves of the space suits.

Already in the earliest stages of the NASA

space program, Leica cameras were part of the equation. One such camera was the Leica Ig. With this camera astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr.,

took the first human-shot, color still photographs of the Earth during his

three-orbit mission on February 20, 1962. Glenn's pictures paved the way for

future Earth photography experiments on American human spaceflight missions.

Because Glenn was wearing a spacesuit,

complete with helmet during his February 20, 1962 mission, he could not get his

eye close to a built-in viewfinder.

Therefore NASA selected the high-quality Leica Ig camera that allowed

them to attach a customized viewfinder on top. This special attachment featured

a suction cup on the back side to allow Glenn to easily place the device

against the visor when he was required to keep it down. The viewfinder was

removable when Glenn did not need his visor down, and a velcro strip on the

rounded top let him manage its location inside the spacecraft. Glenn found the camera easy to use, in part

because he could exploit the advantages of zero-gravity.

"When I needed both hands, I just

let go of the camera and it floated there in front of me," he said in his

later memoir.

The 1957 Leica Ig was the last Leica

screwmount model made, with production ending in 1963. It was the successor to the If and is the

only screwmount camera with the word 'Leica' engraved on the front of the

camera. This camera had the same profile as the IIIg but without the

viewfinder/rangefinder incorporated into the top. As with both the Ic and If there were two

accessory shoes mounted for attaching a separate viewfinder and rangefinder.

The rewind knob was partially recessed into the top plate. As with the Ic and the If, the Ig was

intended for scientific or Visoflex use.

A little known fact is that a Leica M3

accompanied the astronauts on a September 1995 Endeavour space shuttle

mission. As reported by the Houston

Chronicle…

NASA

Photographer Makes History With Trusty Camera

MARK

CARREAU Staff

SAT

02/10/1996 HOUSTON CHRONICLE

Odds

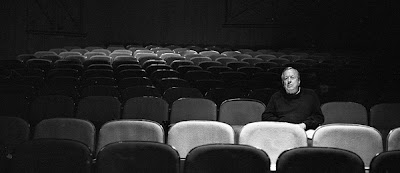

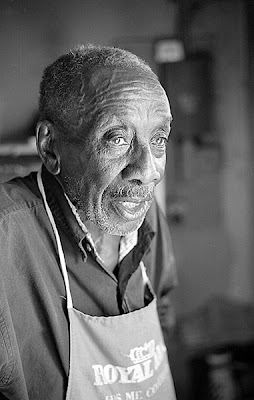

are that Andrew Patnesky, ""Pat" to his colleagues, has used the

vintage Leica camera that swings from his leathery neck like an old dog tag to

photograph every American astronaut since Alan Shepard.

It

was only fitting that the trademark photo gear with the thick rubber band

binding its aging components together accompanied a shuttle crew into orbit

recently, something the 75-year-old NASA photographer couldn't do.

""I

think the world of that camera," said Patnesky, who shuns more modern gear

with the automated features that focus and advance film in favor of the

all-manual Leica M3.

""I

have other cameras, but they don't measure up," he said.

""Anyone can just go shoot. Anyone can be a photographer, but not

everyone can be a photojournalist."

Patnesky

fretted over the Leica's absence during its orbital journey aboard the shuttle

Endeavour last September. The separation was prolonged for several weeks after

the shuttle's return so that the Leica could be unpacked and its journey

officially documented.

""I

feel kind of naked without it," he joked recently, clearly relieved that

the old camera was available once again for his patrols of the space center's

astronaut training facilities.

Patnesky

staked his claim to the government-owned gear when he spotted it in an

equipment closet soon after he joined NASA in 1961. The Johnson Space Center,

then known as the Manned Spacecraft Center, was just beginning to take shape in

Houston.

""None

of the other dingbats would use it. So I said, `Hey, give it to me,' "

recalled Patnesky, who spares no one, least of all himself, from his playful

verbal digs.

Relying

on his 21 years of experience as a photographer with the old U.S. Army Air

Corps and then its successor, the Air Force, Patnesky began to chronicle, with

the trusty Leica, the personalities who led America to the moon.

In

those days, he said, the news media was thirsty for a steady stream of

photographs of astronauts as they trained for their Apollo flights in exotic

locales, from the Gulf of Mexico where they rehearsed post-splashdown

procedures in rough seas to the deserts of Mexico.

During

one of the Mexican excursions - it was a training jaunt by Shepard and

astronaut Edgar Mitchell to prepare for their Apollo 14 flight - an

instructor-geologist challenged Patnesky to descend into a rocky crater for

photographs.

As

he made his way to the crater floor, Patnesky slipped between the boulders. The

Leica's fragile view finder broke away, disappearing between the rocks. Rather

than replace the camera, though, he obtained a new view finder and lashed it in

place with the first of a succession of wide rubber bands, lending the camera

its rag tag character.

To

this day Patnesky finds the Leica perfect for his needs, rubber bands and all.

With

its precise mechanics and acute optics, the old camera makes little shutter

noise and requires no flash when its operator is photographing in the Mission

Control Center, the space shuttle simulator or the administrative offices.

""I

like to shoot on a noninterference basis," he said. ""That is

how you get the best shots."

The

strategy has permitted Patnesky to photograph all of the American presidents

with astronauts from John Kennedy to Bill Clinton. It allowed him to capture

the drama of the Challenger accident as it was reflected in the faces of the

personnel in Mission Control, as well as the majesty of Anwar Sadat, the late

president of Egypt, during a state visit.

His

favorite subjects, though, are the astronauts, from the original Mercury

explorers to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, the first lunar explorers, and now

the shuttle astronauts and their recent Russian cosmonaut guests.

""My

friendship with the astronauts means a helluva lot to me. I admire those guys

for all the hours they put in," said Patnesky. ""One way or

another I've photographed every one of them."

One

of 10 children born to a Pennsylvania coal mining family, he commutes 110 miles

to work each day from a home north of Houston and shares time with his wife in

a second home near San Antonio.

Wiry

and healthy, Patnesky will log his 56th complete year of government service on

Oct. 1. He is coy about his retirement plans.

But

he feels so strongly about his association with the astronauts that he is

willing to part with his Leica when he leaves NASA. He wants it to go on

display at the Astronaut Hall of Fame, just outside the gates of the Kennedy

Space Center in Titusville, Fla.

My continued research into Leica cameras

that were used by NASA has yielded another interesting result. This Leica camera was used in conjunction

with a spectrograph and was used on the Gemini V and VIII missions. Longer

missions during the Gemini program gave astronauts more time for scientific

experiments, often created and monitored by other government agencies or

academic institutions. Scientists at the U.S. Weather Bureau (now NOAA) created

this camera attachment so it could simultaneously record a spectrum and an

infrared image to determine cloud heights.

The camera appears to be a model

M3. It is unknown if any special

modification were necessary for this specialized use.

It is not known if any current Leica

equipment is being used by NASA. The

delay by Leica to introduce top level digital cameras leads me to believe that

other manufacturers might have been chosen.

However, this is an ongoing research project and should new information

become available, you will read about here.