This morning I received a

note wishing me “Happy World Photo Day.”

It then proceeded to proclaim that photography is 177 years old

today. I am quite familiar with the

history of photography and 177 years is not accurate. The actual age of photography is 190

years. Is there an explanation for this discrepancy?

The answer is “sort of”. Even though this is not directly related to

Leica, I think it is still worth looking into because without the invention of

photography there obviously would be no Leica cameras.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

The history of photography

would be incomplete without mentioning Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. He must be credited with having produced the

oldest surviving photograph in 1826. He

had experimented with heliography, as he called it, for quite some time and

finally succeeded to produce a photograph that would not fade after just a very

short time.

From a letter to his

sister in 1816, he talked about having succeeded in producing recognizable

photographs on paper coated with silver chloride. However, he had no means to fix the images,

keeping them from turning black after only a short while. So he looked for other means to achieve his

goal. That led him to use Bitumen of

Judea, a naturally occurring asphalt that had been used for various purposes

since ancient times.

He had some early

successes with this process making contact prints, usually of drawings. But soon he would begin to use a camera

obscura, a device used extensively to make very accurate drawings of scenes

which were displayed by a lens in the camera on a ground glass. Niépce correctly assumed that it should be

possible to capture these images on sensitized pieces of paper.

He had noticed that a thin

layer of bitumen of Judea would harden when exposed to light for a period of

time. Then, after the exposure, he would

use lavender oil, a solvent, to wash away the less hardened areas.

In 1822, he used it to

create what is believed to have been the world’s first permanent photographic

image, a contact print of an engraving of Pope Pius VII, but it was later

destroyed when Niépce attempted to make additional prints from it. The earliest surviving photographic artifact

by Niépce, made in 1825, is a copy of a 17th-century engraving of a man with a

horse. It is an ink-on-paper print, but

the printing plate used to make it was photographically created by Niépce's

heliography process.

From a letter to his

brother Claude we know that his earliest success using a camera obscura

apparently was in 1824. Most of the time

he tried to photograph the scene outside his window. It is not known what happened to these

photographs, the earliest surviving photograph from these experiments dates to

1816. It is now the oldest known camera

photograph still in existence. The historic image had seemingly been lost early

in the 20th century, but photography historian Helmut Gernsheim succeeded in

tracking it down in 1952. The exposure time required to make it is said to have

been eight or nine hours. That

photograph is now in a museum at the University of Texas.

Niépce photograph from 1826, the oldest surviving photograph

Obviously an exposure time

of eight hours is not very practical, to say the least. That problem was partially solved by Louis

Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. He operated

several theaters in Paris with rather elaborate stage scenes which he used to

introduce the impression of movement by moving various theatrical stage paintings

which were produced with the help of a camera obscura. Daguerre had begun to think of directly

producing these via a photographic process.

Louis Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

Louis Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

The largest lens maker at

that time was the house of Chevalier in Paris.

Niépce had contacted them in the past, looking for faster lenses for his

camera obscura to gain shorter exposure times.

Daguerre obtained his lenses from them as well, and they introduced him

to Niépce.

The two decided to

collaborate with the purpose of developing a more practical photographic

process.

Further experiments showed

that Niépce’s process was most likely a dead end, and they decided to look for

different means to produce photographs by going back to plates sensitized with

silver halides, a process Niépce had experimented with in the past . Unfortunately Niépce died in 1833, but

Daguerre continued the research which resulted in the so-called Daguerreotype

process which was officially introduced in 1839.

The process required a

sheet of silver plated copper to be polished to a mirror like finish which

would then be treated in darkness with halogen fumes to make it light

sensitive. After exposure in a camera

obscura, the plates were developed by exposure to mercury fumes. After development, the plates were fixed by

removing the remaining silver halides with a mild solution of sodium

thiosulfate. Depending on the level of

illumination, this process rendered exposure times as fast as just a few seconds;

definitely an improvement.

Still life with plaster casts, made by Daguerre in 1837, the earliest reliably dated daguerreotype

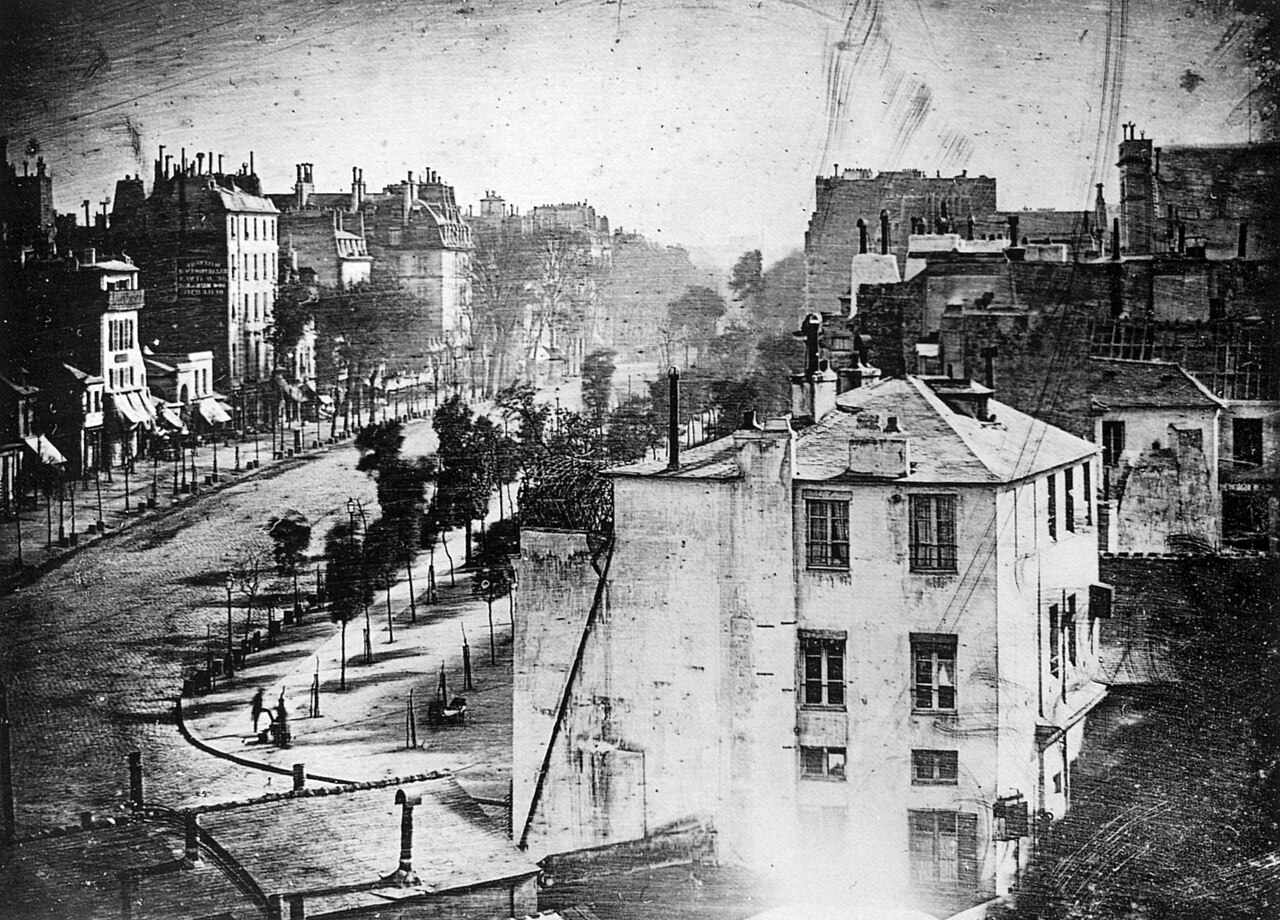

The earliest reliably dated photograph of people, taken byDaguerre one spring morning in 1838 from the window of the Diorama, where he lived and worked. It bears the caption huit heure du matin (8 a.m.). Though it shows the busy Boulevard du Temple, the long exposure time (about ten or twelve minutes) meant that moving traffic cannot be seen; however, the bootblack and his customer at lower left remained still long enough to be distinctly visible.

However, the Daguerreotype

still had one considerable draw back. It

was a direct process which would only render one photograph at a time which

brings us to Henry Fox Talbot of Dorset in the United Kingdom. He is generally credited with inventing the negative

process, not unlike what film photography still uses today.

Henry Fox Talbot

Henry Fox Talbot

Talbot's early "salted paper" or

"photogenic drawing" process used writing paper bathed in a weak

solution of ordinary table salt (sodium chloride), dried, then brushed on one

side with a strong solution of silver nitrate, which created a coating of very

light-sensitive silver chloride that darkened where it was exposed to light.

Latticed window at Lacock Abbey, August 1835.

A positive from what may be the oldest existing camera negative

This process was developed

by Talbot virtually parallel to the Daguerreotype process of Daguerre. However, Talbot was very secretive. He did not want anyone else to know about it

for fear of others using his process to their advantage. It is most likely because of this fear that

Daguerre was able to introduce his photographic process prior to Talbot.

The rest is history, as

they say. All three of these individuals,

however, deserve equal credit for the invention of photography. It is quite astonishing that even now, 190

years later, we essentially use a very similar process. We still use a camera to expose a light sensitive

medium, film or electronic sensor, to produce photographic images. Thank you Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, Louis

Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot.

________________________________________________________________________________________

To comment or to read comments please scroll past the ads below.

All ads present items of interest to Leica owners.

To comment or to read comments please scroll past the ads below.

All ads present items of interest to Leica owners.

For rare and collectible cameras go to: http://www.tamarkin.com/leicagallery/upcoming-shows

For rare and collectible cameras go to: http://www.tamarkin.com/leicagallery/upcoming-shows

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

No comments:

Post a Comment