By Heinz Richter

We have touched on this topic on several occasions. The basic answer is “Yes”. We have also given examples from time to time. But we are certainly not the only ones that make those claims. I came across an article by David Taylor-Huges who discovered some interesting difference among Leica sensors and those of some competitors. He wrote about the performance of the Novoflex Canon EOS adapter for the Leica SL. This gave him the opportunity to compare not only lens performance in general, but interestingly enough the performance of Canon lenses on the Canon 5Ds and the Sony A7rII compared to the Leica SL. He stated:

“I have to say that I found this surprising, but these Canon lenses are super sharp on my SL. The 17-40mm zoom, which gave me only average results on my Canon 5Ds and soft corners on my Sony A7rII is incredibly sharp on the SL. And so are the others, including the 18 yr.old designed 28-135mm. Of particular mention is the 85mm f/1.8, which is spectacularly sharp across the frame. The brilliant little 40mm f/2.8 FF pancake is also very good indeed. As I indicated, I wasn’t expecting this, but Leica’s commitment to non-AA filtered sensors shows it’s benefits here. I’m quite happy to admit that I’ve not been that complementary about Canon EOS EF lenses, but on the evidence of this they are a lot better than I thought. Once you get rid of that AA filter softness that is.

I can’t really speculate why the Sony A7rII ... I used the 17-40mm lens f/4 with was so poor, but it was. Very soft corners and poor overall sharpness. Using the same lens with the Novoflex adapter on the SL has shown me that there is nothing wrong with it, in fact quite the reverse. These are focal lengths I use a lot, so I was pleased to see the results with this lens.”

See the complete article here:

This brings up the question of what it is that allows the Leica sensors to show such performance increases. The elimination of the anti aliasing filter is one thing. While most other manufacturers use such a filter to prevent aliasing problems, Leica does so strictly electronically, with nothing in the way of the light path from the lens. But there is more.

Most people are under the mistaken impression that the higher the megapixel count in a camera, the better the performance. Even though it may appear to defy logic, this is not necessarily the case. Any optical system, even a theoretical one that is made without any optical aberration or other faults, has a performance limit.

With the ever increasing pixel density of digital sensors, an ever increasing number of megapixels are being put in the same space. That brings up the question if our lenses are even capable of a level of resolution to take advantage of the sensor’s capability.

Even the most accurately made lenses have an absolute limit: the physical properties of light.

The resolution of any optical system is limited by diffraction. The light, the aperture and especially the diffraction of the light at the edges of the diaphragm constitute an absolute limit of the overall resolution. It is impossible to achieve a resolution higher than that allowed by the lens, regardless of the resolution capabilities of the sensor or film.

This brings up the question of what resolution a photography system is capable of under ideal conditions. This is a very interesting question in view of the fact that many digital cameras are getting close or even exceed the limits of diffraction – the sensors are of a resolution level that the lenses are hardly capable of achieving. To be clear, this has nothing to do with the quality of the lenses, it is solely because of the limits of physics.

Here is a table of these limits based on sensor size.

The lens opening or aperture is the deciding factor for the resolution capabilities of any optical system. The larger the diameter in relation to the focal length, the larger is the theoretical resolution. Each subsequent smaller aperture will half the visible resolution.

Unfortunately, the performance of most lenses is usually less wide open than when moderately stopped down. The theoretical values at f/1.4 can hardly be reached in the real world. Optimum performance usually is not reached until stopping down to a range of f/2.8 (at best) to f/5.6 or f/8. Please note that due to diffusion within the emulsion these figures extend to f/11 with most color and black and white films.

This is especially important with smaller sensor sizes. While a 35mm full frame sensor is capable of a theoretical resolution of 60 megapixels at f/5.6, a 2/3 sensor is reduced to just 4.4 megapixels at the same aperture.

At this point, the actual pixel size becomes important also. As a rule of thumb, we use Aperture divided by 1.5 equals pixel size in microns or µm (Aperture/1.5=pixel size). For example, 2 / 1,5 = 1,3; 5,6 / 1,5 = 3,7. At f/2, all sensors with a length of 1,3 µm or more on each side are capable of resolving all the lens can deliver, but at f/5.6 the individual pixel size has to increase to a length of at least 3,7 µm to do the same. If the individual pixel size is smaller, resulting in a seemingly higher sensor resolution, we are dealing with a so-called blind resolution which cannot be achieved because of the physical limits of the resolution of the lens.

It must be pointed out once more that these values all are based on theoretically flawless optical systems. Not included are negative impacts from anti-aliasing filters, signal processing (keyword Nyquist Frequency), increases in noise and the necessary interpolation of sensors with Bayer mosaic (RGB filters).

Ultimately it is up to each individual what performance parameters we want to set for or expect from our camera equipment. This article hopefully made it clear that megapixel resolution is not necessarily the key to overall performance of our camera equipment, that lens performance is of equal, if not even greater importance.

This brings us to Leica lenses in particular. Since theoretical resolution is highest at the largest aperture of a lens, it makes sense to use lenses which do offer good performance at those apertures. In this regard Leica lenses are unsurpassed. While competitor lenses might come close in performance to their Leica equivalents at smaller apertures, their performance fall off wide open is usually noticeably greater than with their Leica counterparts. For example, the 180mm f/3.4 Apo-Telyt R was specifically designed to offer optimum performance at maximum aperture. There was no appreciable performance increase at smaller apertures. Other examples are the Summilux f/1.4 lenses and the Noctilux f/0.95. These lenses are capable of taking full advantage of the performance increase when used wide open. We should always evaluate a lens by its performance at ALL apertures and not only the ones that result in the best results. It doesn’t make any sense to buy a fast f/1.4 lens, for instance, if it requires to be stopped down to f/4 or f/5.6 to deliver adequate results.

Leica 180mm f/3.4 Apo Telyt-R and 50mm f/0.95 Noctilux

While these are compelling reasons for considering Leica cameras and lenses, their sensors do set themselves apart from the competition also. Instead of participating in the pixel race, Leica and their sensor manufacturer have done a remarkable job of optimizing sensor performance. Not until recently did Leica offer a few of their models with a sensor resolution greater than 24 MP and even now, the majority of their cameras offer a resolution of 24 MP.

Compared to other companies, both the Leica M and S line of cameras seem to be lagging behind some of the cameras of their competitors. However, that does not at all translate into lesser performance and capabilities and their competitors are aware of this as well. Until recently, most high end cameras on the market had settled on a pixel count of approximately 20 to 25 MP. But the Leica sensors differ in several respects, all of which are designed to optimize performance. Besides, what is really gained by a higher pixel count?

Take the old Leica S sensor for instance. The difference between the 37.5 MP sensor of the Leica and a 50 MP sensor is only 10 – 15% as far as the increase in linear resolution is concerned. Is that really enough of an increase compared to the other advantages of the Leica MAX 24MP CMOS Sensor as used in the Leica M? Let’s take a closer look.

It is no secret that individual pixel size does make a difference. The larger the individual pixels, the better they will perform. To increase resolution, either the pixels need to be made smaller to fit into a certain sensor size, or the sensor size needs to be increased.

Regardless of the number of pixels on a sensor, not the entire surface area of each individual pixel is light sensitive. The pixels need to be supported by a substructure and each individual pixel needs to be connected to the system by small wires. Canon, for instance uses wires with a size of 0.35 micron. Sony is definitely better with a size of 0.18 micron. Leica by far exceeds that with a size of 0.09 microns. As a matter of fact, when determining the specifications for the sensor, Leica demanded that the structure sizes be kept as small as technically possible.

One goal was to keep the non-sensitive areas of each pixel as small as possible. If less of the surface of the sensor is taken up by supporting electronics overhead, then more surface area can be used to collect incoming light. This results in greater dynamic range and a higher initial sensitivity.

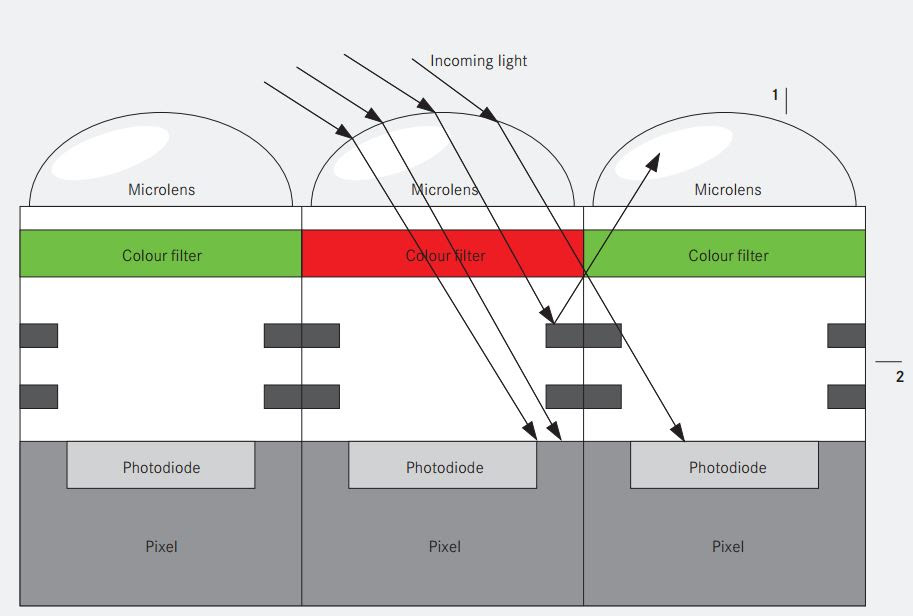

The surface of a sensor. If the non-sensitive areas can be made as small as possible, more surface area is gained to collect light. Image courtesy of

Leica Store Miami

Another means to increase sensor performance is to make it as thin as possible. At its introduction, the Leica CMOS sensor in the Leica M240 was the thinnest ever developed. Each sensor contains several layers. By making each of them as thin as possible, the end result is a significant increase in performance because more of the incoming light can actually reach the photodiodes, the individual pixels.

Another advantage was gained by using copper for the connecting material instead of aluminum, which is the common choice because the process of using copper is substantially more complex. Copper has a substantially lower electrical resistance than Aluminum, meaning that conducting layers with half the thickness could be used. In addition, to minimize thickness, instead of having four metal layers for the conductors typically employed on CMOS sensors, only two were necessary on the MAX CMOS chip.

An advantage was also gained by using a different design for the microlens covering the entire sensor. Instead of using the common flat lenses, Leica went to an elongated, parabolic design. That has the advantage that more of the incoming light will be redirected to the individual pixel areas and, especially at the corners of the sensor, there will be no noticeable vignetting.

Conventional CMOS sensor with deep pixel wells and flat microlenses

Leica CMOS sensor with very shallow pixel wells and tall micro lenses, allowing for larger pixel area

This can easily be verified. Several other camera manufacturers allow the use of Leica M lenses on their cameras. Take the Sony A7r for instance. Mount a Leica 18mm Super Elmar-M ASPH on the Sony and take a few test shots. Then compare those to the results obtained from a Leica M. The difference is more than obvious. But it doesn't even require an extreme wide angle lens like that. Take a 35mm Summilux ASPH, and you will find similar difference. The Sony sensor just isn’t capable of handling non-retrofocus lenses anywhere near as well as the Leica M does.

However, it must be noted that some of the drawbacks and disadvantages described can be overcome by electronic trickery. Take modern mobile phone cameras for example. They naturally have rather small sensors because of the size of the phones. Yet their performance level is actually quite remarkable. We have even seen mobile phone camera with rather high pixel counts of 40MP or more. Yet with all the electronic wizardry, none has ever come close to the performance of a good full frame or even APS sensor size camera.

Therefore, when it comes to selecting a high performance camera system, one has to consider the draw backs of trying to overcome physical and optical disadvantages with electronic “band aids” and one also has to take into consideration if a gain of a few pixels per inch in linear print resolution is more important than the long list of advantages gained with a Leica MAX CMOS sensor.

For other articles on this blog please click on Blog Archive in the column to the right

To comment or to read comments please scroll past the ads below.

All ads present items of interest to Leica owners.

_______________________________________________________________________

EDDYCAM - the first and only ergonomic elk-skin camera strap

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

Click on image to enlarge

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

Click on image to enlarge

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

I would like to see a much better explanation of the table called "Maximum Number of Possible Megapixels". I understand very well what diffraction is, both at the level of the sensor and the diaphragm, but why does it drop by half with every F-stop? I would expect it to be much more non-linear, and to be negligible up to F8.

ReplyDeleteDepending on the size of the actual diaphragm opening, diffraction is negligible up to a certain f/stop. That, however, diminishes as the diameter decreases. That's why with wide angle lenses, that f/stop will inevitably be a wider one since the actual aperture opening with wide angle lenses is smaller at all apertures to begin with. The possible megapixels diminish with each aperture because the effect of diffraction becomes more prevalent when the actual opening becomes smaller. The amount of diffraction remains roughly the same, but the overall area of the aperture opening gets smaller, of course, meaning that the effect increases. The next time I have an opportunity to talk to Peter Karbe, head lens designer at Leica, I will ask him for a better explanation.

DeleteDrop a marble in a bowl of water, and watch the "ripples" bounce off the sides. Drop a marble in a lake, and watch the ripples bounce off the sides. The large distance between sides to other areas (i.e. middle / opposite side), means the amount of disturbance (wave motion of the ripples) has a lesser effect on the larger distances.

ReplyDeleteWhile photons remain a fixed size ... the larger (physical) aperture will have greater distances from edge to edge or edge to center for which the "bouncing" wave action to dissipate. As amplitudes of wave action combine / offset from the photons, it makes things "choppy", like the wakes of two boats intersecting.

The closer those two boats pass by one another, the stronger the amplitude of the colliding wakes. If those boats originate their wake from distances farther from one another, by the time the wakes intersect, the amplitude of their wave motion is less than when originated closer together.

Since photons travel in a "wave-like" motion, each photon travels like a wake. The more collinear their travel is, the less intersection of waves occurs. Smaller (physical) apertures (bowl vs. lake) will induce more "choppiness" to reduce the crispness / clarity of the image, since the "bounce" off the aperture blades are closer together. This is in part why MF cameras have less issue with diffraction at "small" apertures. Their apertures may be "small" as a ratio of light area through the entrance pupil to the area of the image circle ... BUT, their physical dimensions are larger, so there is a greater distance of the perimeter (where the diffraction originates) across the aperture, which also means more collimated photon travel to be less impacted by diffracted (re-direction) photon travel.

Marbles / boats in different size / proximity bodies of water are the most representative example of the effects of diffraction that come to mind, atm.