By David Farkas, Leica Store Miami

As a landscape photographer, I’m always looking for an edge. Light is fleeting, and those elusive magical moments that we venture untold distances for often last for just an instant. In my experience, the best defense against missing the shot of a lifetime is a good offense, photographically speaking. That means knowing your gear and being prepared. Understanding the performance envelope of your camera, its capabilities and limitations, lets you approach any situation with confidence. The second part of the equation is being prepared and having the right tools for the job. A camera that delivers malleable and visually appealing files. A sturdy tripod and head. Focal lengths that work for the scene. And, you guessed it, filters.

Digital changed everything most things

In the golden age of film, filters were kind of a big deal. Warming filters, color filters, skylight filters, haze filters, star filters, and more found their way into many a photographer’s camera bag. Film was generally daylight balanced and filters were the only way to alter the color captured, especially on slide film, the widely preferred medium for serious landscape photography. With the advent of digital cameras and post capture adjustable white balance, a whole category of photographic accessories become obsolete and unneeded.

So, why are we even talking about filters here? Can’t everything just be done digitally? Well, yes. And, no. Most filters are not useful for digital photography. But, there are certain feats even the best camera just can’t do by itself. Let’s take a look at a few of these cases and what tool we can put to use to solve each one.

Neutral Density filters and shutter speed limits

If you want to get a long exposure to blur moving water, the lens can only stop down so far at base ISO. According to the Sunny 16 Rule (remember that one?), at ISO 100 and f/16, your shutter speed will be 1/125th of a second. Even in partial shade, which is around 2-stops less, you’re still limited to 1/30th of a second, which is not long enough. Besides, you shouldn’t be shooting at f/16 on modern digital Leicas. Do yourself a favor and stick to f/11. This avoids the softening effects of diffraction and still provides ample DOF. But, being limited to f/11 also puts us another stop in the hole when we want slow speeds.

Leica S (Typ 007) with 30mm Elmarit-S

1/60 sec @ f/11, ISO 100, no filter

ND filters are the secret weapon to take control of shutter speed. If we’re lining up a shot of a waterfall in the shade, getting an exposure of 1/60th of a second at f/11, ISO 100, and pop a 6-stop ND on the front, the resulting shutter speed of 1 second lends itself so much better to achieving the desirable cotton-candy effect. Need more time? Once shutter speeds start going in to the whole second range, those times will increase dramatically with each additional f-stop of filtration. With just 2 more stops of ND, the 1 second exposure jumps to 4 seconds.

Leica S (Typ 007) with 30mm Elmarit-S

1 sec @ f/11, ISO 100, 6-stop ND

ND, or Neutral Density, filters simply reduce the amount of light coming in through the lens. Think of them like sunglasses for your camera. Each stop of ND will cut the light by half, meaning that we need to double the shutter duration to make up the difference. A 4-stop lets in only 1/16th of the light in. By 6-stops, only 1/64th of the illumination is getting through the lens. Very powerful 10-stop filters block all but 1/1000th the amount of light.

A 12 second exposure is long enough to blur ocean waves into a smooth surface

Leica S (Typ 006) with 30mm Elmarit-S ASPH

12 sec @ f/11, ISO 100, 10-stop ND

For this reason, you might also see filter strengths indicated by their power, such as 64x for a 6-stop or 1000x for a 10-stop. And yet another designation can be expressed in optical density, where 6-stop and 10-stop filters would be labeled 1.8 and 3.0 respectively. The easy way to decipher the optical density is to just divide by 0.3, as each 0.3 increment is equal to one f-stop of EV reduction. Here’s a table to break it down for you:

f-Stop Reduction Optical Density ND Strength Light Passed

1-Stop 0.3 2x 1/2

2-Stops 0.6 4x 1/4

3-Stops 0.9 8x 1/8

4-Stop 1.2 16x 1/16

5-Stops 1.5 32x 1/32

6-Stops 1.8 64x 1/64

7-Stops 2.1 128x 1/128

8-Stops 2.4 256x 1/256

9-Stops 2.7 512x 1/512

10-Stops 3.0 1000x 1/1024

ND filters come in both thread-mount and 4” square formats. On M cameras where you’re using a rangefinder and not looking through the lens, thread-mount work fine. For other cameras, I’d suggest sticking with the 4” square variety which can be toggled on and off the lens for composition and framing much more easily.

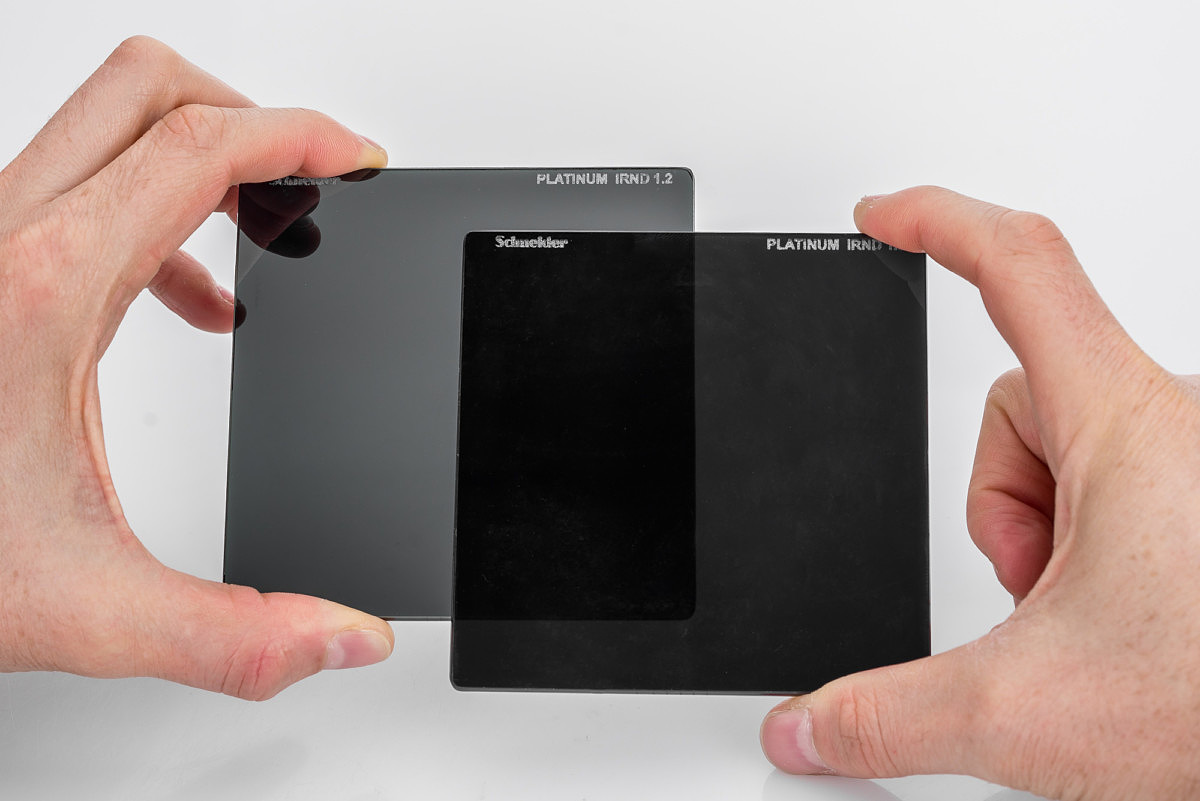

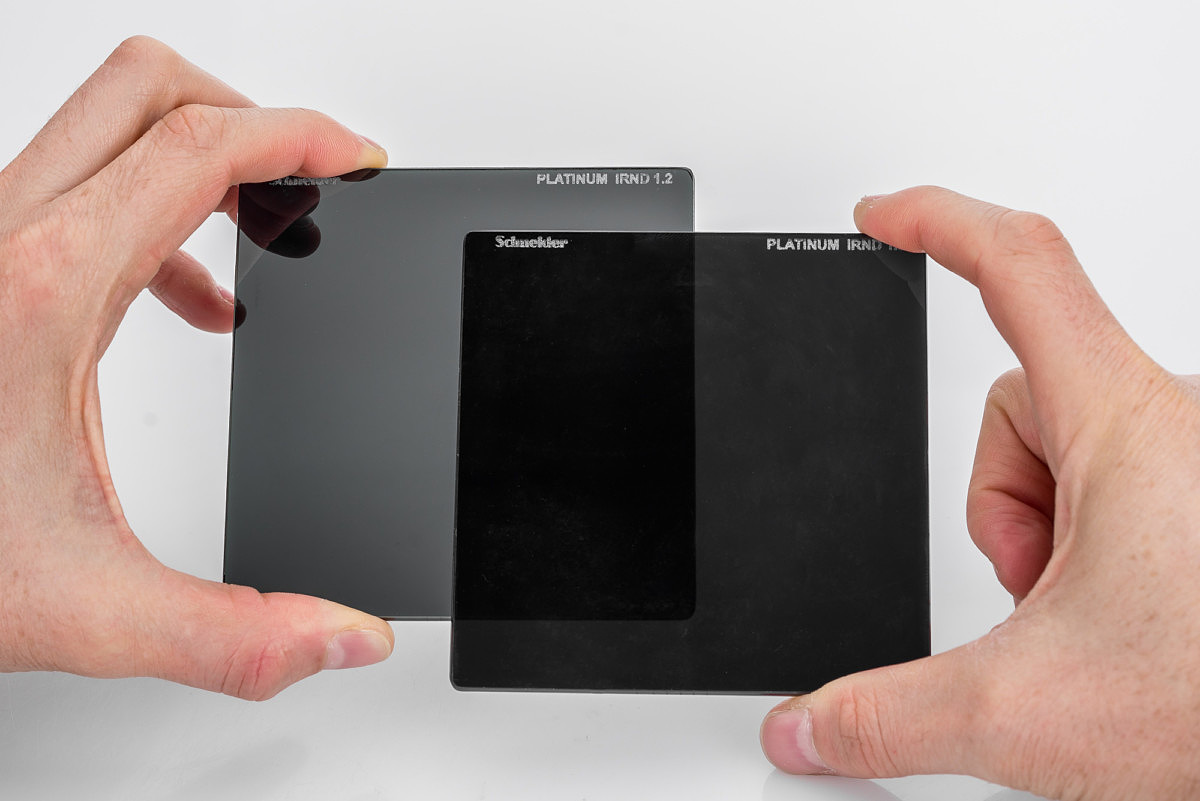

4-stop and 6-stop Schneider Platinum IRND filters in 4″ square size. When stacked, their ND effect is additive, creating a 10-stop ND

IR bleed

One issue that has plagued ND users is a quirk of physics. ND filters do a great job of blocking the visible light spectrum but are terrible at keeping out IR wavelengths. IR and near-IR bleed creates strong reddish-magenta casts on your images which are difficult to correct. The stronger the ND strength, the more evident this becomes, as the relative proportion of IR exposure increases exponentially.

IR bleed on a 16 second image with non IR-blocking filter

Luckily, in recent years, Schneider released their line of Platinum IRND filters. As the name suggests, the filters effectively cut IR at the same levels as visible light, yielding much more color-neutral results.

The problem with dynamic range

When we watch a gorgeous sunrise, with the sun breaking over the horizon, our eyes and brains work together to see detail in both the intensely bright sun as well as the deep shadow of the backlit foreground. Unfortunately, even the best camera is no match for the human eye with regards to dynamic range. A detailed foreground with a blown-out sky doesn’t make for dramatic landscape images, nor does the reverse.

Exposing for shadows results in blown-out sky

Exposing for the sky results in dark foreground

The solution(s) – HDR or GND

So, we’ve got two approaches. One is digital, the other analog.

Bracketing and HDR

We could employ auto bracketing, whereby the camera takes a series of pictures spaced at user-selectable exposure intervals by varying the shutter speed for each capture. A three-shot bracketed sequence like the one below consisted of -2, 0, and +2 exposure compensation, giving you three DNG files which must then be combined in Lightroom to a single HDR DNG. This technique essentially expands the dynamic range of the camera by the total exposure gamut of the sequence. In the case of our example values of -2 to +2, we adding 4-stops. And, the results with proper processing, can be quite good as you can see here.

A 3-shot HDR blended in Lightroom

On a Leica SL with a native 13-stop DR, this technique expands the range to 17-stops. You can go much further than this, shooting up to a five-shot sequence with 3-stop spacing and getting from -6 to +6, resulting in a total DR of 25-stops. While possible, 3-stops is a very sizeable gap. If you do go this route, 2-stop spacing is more realistic, resulting in a total DR of 21-stops. As far as the downside, you’re also tripling or quintupling the number of pictures you’re capturing, storing, downloading and processing.

Graduated ND filters

The second option is to kick it old school, by using a GND or Graduated Neutral Densityfilter. GND filters transition from a full ND filter like we discussed in the previous section to a clear optical glass section with no correction. Commonly made in a rectangle measuring 4” across by 4.65” in length, the filter can be slid up and down in a holder on the front of the lens to match up to the scene, effectively applying ND to only bright sections of an image. The holder clips onto a metal adapter ring, which is screwed onto the filter threads of your lens.

Schneider 4-stop Soft Edge GND slides easily into filter holder

Instead of taking three pictures with a 2-stop spacing for a 4-stop gain and combining in Lightroom, we can just use a 4-stop GND and take one picture. A big advantage of this approach is that you can see the final image in the viewfinder and on playback. The filter can be adjusted in real time to suit the scene. With this technique, you don’t need to shoot multiple images for every scene. For longer exposures, this can be time consuming, drain your battery, fill up memory cards quickly and sometimes cause you to miss the shot. If the scene has moving elements, like rushing water, blending can be tricky.

By using a GND, there is only a single capture of the moving water, rather than three images with different shutter speeds.

The carpenter’s adage of measure twice, cut once comes to mind. A GND lets you get the shot right in camera. And once you have the filter positioned, you can shoot at will as the light changes.

They come in two varieties. A soft edge GND features a gradual, soft transition from full ND to clear. A hard edge GND has a much shorter gradient with barely any feathering. Soft edge is most useful for busy or uneven horizons, where the effect blends more naturally into the scene. Hard edge is best for crisp horizons like an ocean or lake. A combination of both is ideal.

Filter strengths of 2, 3 and 4 stops are available. Personally, I find the 2 stop a little weak in most circumstances. My suggestion is to grab a 3 or 4 stop.

Circular Polarizers and the problem with reflections

One of the few filters that can’t be replicated in post processing is a circularpolarizer. Many people think of a polarizer as that dark grey filter that rotates, darkening and saturating blue skies while making white puffy clouds pop, and they’d be right. Polarizers do have that effect and have been beloved by landscape photographers for ages.

Polarizers can make colors and skies pop

But, a polarizer is much more than that. In fact, I rarely use them to create dramatic skies. With HSL controls in Lightroom, a similar look can be had with a few seconds work. And, given the physics of polarization, this sky pop only works at 90 degrees off-axis from the sun. In practical terms, polarization won’t work shooting into the sun or with the sun at your back, only to your left and right. A tool that only works 50% of the time isn’t a great one to count on.

Rather, I use polarizers to eliminate reflections on surfaces, something Lightroom can’t do. Number one use case: waterfalls. Waterfalls have a lot of water and generally a lot of wet rocks around them. White, shiny rocks with little detail aren’t as attractive as darker, more detailed ones. Give the polarizer a spin until the glare goes away in the viewfinder. Done.

By eliminating reflections, a polarizer takes the shine off the rocks and brings out the color in the water. A 6-stop ND then allows for a long 3-second exposure.

They also do a nice trick for foliage. Waxy leaves in the sun tend to wash out. To take foliage photos to the next level, use a polarizer for rich, saturated colors.

In this case, the polarizer removed the reflections from the light branches and off the leaves, giving great contrast and color saturation

Be aware that most circular polarizers will knock down your exposure by 1.5 to 2.5 stops depending on the amount of polarization. This can actually come in very handy for those aforementioned waterfalls, either giving you a slow enough shutter speed to blur the water in the shade or stacking nicely with a 6-stop ND for 8-stops and maximum blur under any condition.

Or, if you are concerned with keeping your shutter speeds up when using a polarizer, B+Woffers an HTC, or High Transmission Circular, version of their popular filter. New high transmission polarization foil allows more light to pass, resulting in just 1 – 1.5 stops of exposure loss.

B+W KSM Circular Polarizer on left, B+W KSM HTC Circular Polarizer on right. The HTC is about one stop brighter.

Stacking filters for complex scenes

Each one of the previously discussed filter types solves a unique problem. But, what if you have a compound challenge like a scene that needs both a GND to fix foreground/background exposure differences and a solid ND to get a longer shutter speed for water blur? No problem.

No filter – underexposed foreground

The 4”filter holder has two slots for a reason. Slide in the grad filter first so you can see the effect in the viewfinder.

With GND filter, we can equalize the exposure between the foreground and background.

Then, when you’ve got the shot balanced and composed, add in the ND to lengthen the exposure time. Once the ND is added, you might not be able to see much, although I’ve found the Leica SL viewfinder does a fairly incredible job at cranking the gain in the EVF so you can actually see an image. At least in decent light.

Sliding a 4-stop IRND in front of a 4-stop GND for two effects on a single image

With GND and 6-stop IRND to create a sense of motion

Leica S (Typ 007) with 24mm Super-Elmar-S ASPH

1 sec @ f/11, ISO 100

And, if you encounter a super tricky spot where a polarizer is needed, we can make that work, too. The key is to attach the polarizer to your lens first, dial in the effect to taste, then mount the 4” holder’s adapter ring to the filter threads of your CP. Same as above, add in the GND next, and the ND last.

First, I used a polarizer to dial in the reflection of the fall colors in the water, then added in a GND to even out the exposure from the brightly lit trees and the shadowed riverbed

What’s in my bag?

Here’s what I carry in the field for landscape photography. You may notice a bit of wear and tear on this gear, the result of continued use over the years.

My full filter kit

While this might look like a lot of fragile glass to cart around, once each piece is stowed in its respective padded case, everything stacks together and fits neatly in the top section of my photo backpack.

All the filters come in padded cases

My primary go-to camera for landscape photography is the Leica S (Typ 007). The S lenses feature 72mm, 82mm, and 95mm front diameters, so I carry two B+W F-Pro KSM Circular Polarizers, one E72 and one E82. Two filters cover all my lenses except the 24mm Super-Elmar-S, the sole lens in my kit with a 95mm filter thread. Because the coverage of the lens is so wide, I’ve found that polarization can get a little weird in many circumstances. If you’ll recall that the effect works in 90-degree angles, you might imagine what happens in a lens that offers a greater-than-90 degree field of view. This isn’t always the case, as you can see here.

Leica S (Typ 007) with 24mm Super-Elmar-S, Circular polarizer

With one Schneider 4” filter holder and adapter rings for 72mm, 82mm and 95mm I can add GND and ND to my entire lens arsenal. The rings screw onto the front thread of the lens, then the filter holder clips onto the ring. For vertical shooting, or for angled horizons, the filter holder can be rotated freely around the ring.

Mounting an 82mm adapter ring on the lens

The 4″ filter holder mounts to a groove in the adapter ring with teeth on one side and a retractable brass latch on the other. It’s very easy to take on and off during shooting.

For GND, I carry one Schneider GND Soft Edge Vertical 1.2 (4-stop) and one Schneider GNDHard Edge Vertical (4-stop), allowing me to handle most situations. Rounding out the setup are my solid ND filters, aSchneider ND 1.2 (4-stop) and a Schneider Platinum IRND 1.8 (6-stop). Why two? Having both a 4 and 6 stop ND gives me flexibility and a degree of shutter speed control. I can get 4, 6 or even 10 stops by stacking the two filters together.

ND effect is additive

I really like the Schneider 4” filter system. The filters are dense and durable, comprised of two pieces of German Schott Waterwhite optical glass sandwiched together. Unlike less expensive resin filters, glass can be cleaned with a regular lens cloth and does not get statically charged.

The Schneider filters are as tough as the camera

Wrapping up

Filters are an essential part of my landscape photography kit, offering creative options that just aren’t possible without them. When I’m out on assignment or leading a workshop, my filter kit is always at the ready. Often, I have a couple filters and a holder stashed in the front pockets of my technical shell jacket. They can make the difference of nailing an epic shot or coming home with a frustrating near-miss. stashed in the front pockets of my technical shell jacket. They can make the difference of nailing an epic shot or coming home with a frustrating near-miss.

For other articles on this blog please click on Blog Archive in the column to the right

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

Buy vintage Leica cameras from

America's premier Leica specialist

Buy vintage Leica cameras from

America's premier Leica specialist

http://www.tamarkinauctions.com/ http://www.tamarkin.com/leicagallery/upcoming-show

Buy vintage Leica cameras from

America's premier Leica specialist

http://www.tamarkinauctions.com/ http://www.tamarkin.com/leicagallery/upcoming-show

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

Click on image to enlarge

Order: info@gmpphoto.com

Please make payment via PayPal to GMP Photography

No comments:

Post a Comment